Contact Light

SHIPLOG #0009 T+2120-05-18T16:46:50.105823 So here it is. The moment of truth. Will he or won’t he. Explode on impact, I mean… anyways it’s now or never at this point. I’ve got everything I need for a good landing. I’ve got my guidance and navigation. All that’s left is control. That’s a big question, how do I follow the trajectory I’ve generated once it’s time to actually turn on the engine? Well there are lot’s of complex ways to do this that involve deriving the dynamics of my ship, but thanks to my trajectory optimizer, I don’t have to get that complicated! A linear quadratic regulator is sufficient for this task. Time to get started.

Optimal Control

The idea behind a linear quadratic regulator (LQR) is pretty simple. Say I have a state vector representing the error in my state, is there some constant matrix K that will efficiently drive the error to 0? Now LQR has a very big assumption, namely that my system can be represented linearly. Of course the system is highly linear, but there are some tricks I can do to linearize or approximate the system in a linear way such that I can find a K matrix that is good enough.

The first thing I do is split up vertical and horizontal control. The primary reason for this is that it makes the system slightly easier to linearize. I’ll consider the vertical control first. I can create a state space representation of my system. My vertical state is just \(x = [v, \dot{v}]\). (Really my vertical direction is in the x vector direction, but the standard format for state space uses x to represent the full state vector so I’m instead calling the vertical axis v for now) The differential equation of the dynamics should be familiar:

\[\ddot{x} = -g\hat{v} + u\]where u is the thrust vector. Now I need to convert these to a linear state space representation. This means they should follow the form

\[\frac{d}{dt}x = Ax + Bu\]Where x is the state and u is the control. SO I need to convert my equation above into this form:

\[\frac{d}{dt}x = \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 1\\0 & 0\end{bmatrix}x + \begin{bmatrix}0\\1\end{bmatrix}u\]You may notice I haven’t even included gravity (LQR can’t handle constant offset terms like gravity). This literally just says that the acceleration is due to the thruster (controlled with u) and it assumes the thruster is always pointed vertically. Now of course this isn’t great as gravity will accelerate the ship downwards and this won’t account for that. To correct that, I use a simple trick: feed-forward control. Now I know exactly how much gravity accelerates my ship downwards and I can just simply add this to the final control output. Because my controller expects there to be no gravity, if I just add it in to the final output control it will be as if there’s no gravity at all (and the ship should hover in place when no other forces or controls are applied).

Now on to horizontal control. This is a little trickier as it’s really a function of the angle of the ship. My state for this is going to look like \([x, y, \alpha, \beta, \dot{x}, \dot{y}, \dot{\alpha}, \dot{\beta}]\)

\(\alpha\) is my angle in the y direction and \(\beta\) is my angle from the z direction.

I have a pretty big nonlinearity here though which is a problem. My acceleration in the y/z directions has two nonlinear parts. For example, the acceleration in y looks like:

\[\ddot{y} = T sin(\alpha)\]Where T is the acceleration due to thrust. The sine function is nonlinear and multiplying that result with the control vector of thrust is ALSO nonlinear. To correct this, I use two tools for linearizing functions. First I linearize the thrust around a stable point. In this case, I assume thrust is always g because that’s where the accelerations cancel out. Next I use what’s called the small angle approximiation which says \(sin(\theta) \approx theta\). When the angle is close to 0 and the thrust is close to g, this controller will actually work pretty well! The final state space looks like this:

\[\frac{d}{dt}x = \begin{bmatrix} 0_{4x4} & I_{4x4} \\ g_{2x4} & 0_{2x4}\\0_{2x4} & 0_{2x4} \end{bmatrix}x + \begin{bmatrix}0_{6x1} & 0_{6x1}\\aI & 0\\0 & bI\end{bmatrix}u\]where \(g_{2x4} = \begin{bmatrix}0 & 0 & g & 0\\0 & 0 & 0 & g\end{bmatrix}\)

and I is the identity matrix.

u, in this case, is the torque in the \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) directions. aI and bI are the max torque divided by the inertia in that axis. So when I multiply the control torque with this value it gives me the angular acceleration.

The last part of lqr is the Q and R matrices which allow me to tune how I want the controller to behave. The diagonals of the Q matrix tell the controller how important it is to reduce the error in that particular state and the diagonals of the R matrix tell the controller how important it is to minimize energy use.

A few things to note about this controller, it’s probably not going to work well for very high speeds and high levels of drag. There are more suitable controllers, but in this case, this will do for this landing. Now as for solving for the K matrix, python has a nice library to do just that. This isn’t the best solution, but it is more than sufficient for my purposes. The big thing I’ll have to deal with is the ship will handle very differently at high speeds due to drag, but that’s all right. Once it slows down enough it should correct any error accumulated due to drag’s effect on the controller (basically once we’re closer to the point we linearized on!).

Putting it all together

I add the following to my autopilot class:

def do_landing_burn(self, goal_position, do_plot=True):

flight = self.vessel.flight()

orbit = self.vessel.orbit

# x is the vertical position in the g-fold trajectory, so I need to create a new reference frame,

# that's rotating with the planet and has x sticking directly up from my goal.

x_ax = goal_position / np.linalg.norm(goal_position)

y_ax = np.cross(x_ax, np.array([0, 0, 1]))

z_ax = np.cross(x_ax, y_ax)

y_ax /= np.linalg.norm(y_ax)

z_ax /= np.linalg.norm(z_ax)

rot = np.column_stack([x_ax, y_ax, z_ax])

q = R.from_matrix(rot).as_quat()

ref_frame = self.conn.space_center.ReferenceFrame.create_relative(self.body.reference_frame,

position=goal_position,

rotation=q)

# Solve the gfold problem based on current position and velocity

pos, vel = self.get_position_and_velocity(ref_frame)

start_time = self.conn.space_center.ut

config = self.create_gfold_config()

x, u, gam, z, dt = gfold_solver.solve_gfold(config, pos, vel)

# This creates a nice smooth interpolation of my trajectory

timesteps = np.linspace(0, x.shape[1]*dt, num=x.shape[1])

f = interp1d(timesteps, x[:], kind='cubic')

# Ensure all of my autopilot commands are in the new reference frame

self.autopilot.reference_frame = ref_frame

self.autopilot.engage()

# Thrust controller

Qmat_T = np.diag([1, 10]) # favor reducing vertical velocity above all

Rmat_T = np.diag([1])

K_vertical = rocket_control.thrust_controller(self.body.surface_gravity, Qmat_T, Rmat_T)

# Horizontal controller

# Set 0 on the angles for their cost as I don't really care about where they are. It's x/y that I care about

Qmat_h = np.diag([10, 10, 0, 0, 500, 500, 0, 0]) # Significantly favor reducing vertical velocity

Rmat_h = np.diag([5, 5])

MOI = self.vessel.moment_of_inertia

torques = np.abs(self.vessel.available_torque[0])

aI = torques[0] / MOI[0]

bI = torques[2] / MOI[2]

K_horizontal = rocket_control.angle_controller(self.body.surface_gravity, aI, bI, Qmat_h, Rmat_h)

last_angles = np.array([0, 0])

last_time = 0

final_time = x.shape[1]*dt

while self.vessel.situation != self.conn.space_center.VesselSituation.landed:

index_time = self.conn.space_center.ut - start_time

if last_time == cur_time: # this helps prevent divide by 0 instances (like when the sim is paused)

continue

goal_position = f(clip(index_time, 0, final_time)) # get the interpolated goal coordinate

pos, vel = self.get_position_and_velocity(ref_frame)

err = goal_position - np.array([*pos, *vel])

u_v = np.dot(K_vertical, np.array([err[0], err[3]])) + self.body.surface_gravity # add the feed-forward offset term

if u_v < 0: # Can't have negative thrust

u_v = 0

# There isn't a nice way to extract alpha and beta (and their derivatives) so we have to do that ourselves

direction = self.vessel.direction(ref_frame)

alpha = np.arctan2(direction[1], direction[0])

beta = np.arctan2(direction[2], direction[0])

av = (alpha - last_angles[0]) / (cur_time - last_time)

bv = (beta - last_angles[1]) / (cur_time - last_time)

last_angles = np.array([alpha, beta])

# alpha, beta, etc. are negative because the input to LQR is reference - actual. The 'reference' for the angles is 0

horizontal_states = np.array([err[1], err[2], -alpha, -beta, err[4], err[5], -av, -bv])

horizontal_controls = np.dot(K_horizontal, horizontal_states)

# Euler integrate the angles to find the new goal. Can't really actuate the torques directly with kRPC!

# Clip the angles at pi/3 to ensure they don't go below horizontal. The linearization will cause weird things otherwise!

# Also this is using the horizontal control value as the angular acceleration which isn't really true, but it is proportional

# so it works just fine.

new_alpha = clip(alpha + horizontal_controls[0] * (cur_time - last_time), -np.pi/3, np.pi/3)

new_beta = clip(beta + horizontal_controls[1] * (cur_time - last_time), -np.pi/3, np.pi/3)

control_vector = np.array([1, np.tan(new_alpha), np.tan(new_beta)])

self.autopilot.target_direction = tuple(control_vector)

new_throttle = np.linalg.norm(u_v * self.vessel.mass) / self.vessel.max_thrust

self.vessel.control.throttle = new_throttle

last_time = cur_time

self.vessel.control.throttle = 0 # We've landed, turn of the throttle

I also created a new rocket_control module that uses the python control library to generate the K matrices:

import control

import numpy as np

def thrust_controller(g, Q, R):

# States are x and x_dot (x being the vertical direction)

# Control is thrust acceleration

A = np.array([[0, 1], [0, 0]])

B = np.array([[0],[1]])

K, S, E = control.lqr(A, B, Q, R)

return np.array(K)

def angle_controller(g, aI, bI, Q, R):

# States are y, z, alpha, beta, y_dot, z_dot, alpha_dot, beta_dot

# Controls are aI, bI

# aI and bI can be calculated with the max torque on an axis divided by the inertia on that axis

# Thrust linearized to g; sin(alpha)/sin(beta) linearized to alpha/beta

A = np.array([[0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0],

[0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0],

[0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0],

[0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1],

[0, 0, g, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0],

[0, 0, 0, g, 0, 0, 0, 0],

[0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0],

[0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0]])

B = np.array([[0, 0],

[0, 0],

[0, 0],

[0, 0],

[0, 0],

[0, 0],

[aI, 0],

[0, bI]])

K, S, E = control.lqr(A, B, Q, R)

return np.array(K)

And now the moment of truth. Here we go.

Down.

Down.

Down.

Contact Light.

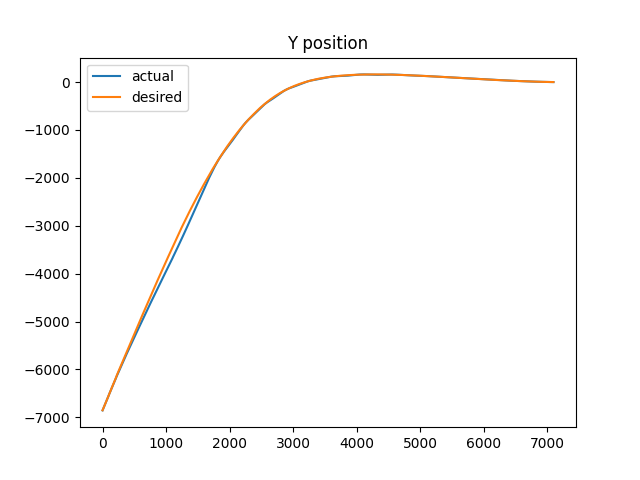

I’ve made it. Let’s see how my controller did:

Not too bad actually! The controllers almost perfectly followed the goal trajectory. (as a side note, I tested this controller in various cases and for velocities <300m/s it did well, but there was a ton of overshoot for everything over that)

The sun is rising over my new lonely home

This is just the beginning of my journey.

-/EOT/ - MC

sources

- https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLMrJAkhIeNNR20Mz-VpzgfQs5zrYi085m - if you want to know more about control theory and a great leadup to LQR this is a fantastic resource